Is love the same across time and around the world? Not so, says Eric Selinger—and what counted as love in one time or place might get you locked up in another! To understand just how many things “love” can mean, Selinger says we need to “go to anthropologists, historians, sociologists, people for whom difference is everything.”

If there are universal attributes to love, they must reside somewhere deep in our biological inheritance. Biological anthropologist Helen Fisher studies love across cultures, and does brain scans of lovers at all stages in relationships. Here’s her TED talk on the findings.

From a Pompeiian fresco popularly said to portray Sappho

“Iridescent-throned Aphrodite, deathless

Child of Zeus, wile-weaver, I now implore you,

Don’t—I beg you, Lady—with pains and torments

Crush down my spirit...”

The ancient Greek poet Sappho lived well over 2500 years ago, but her vibrant “Hymn to Aphrodite” still captures the heady delights of a love based on endless pursuit, not on settled coupledom. There’s no first love in Sappho’s hymn, and no HEA; if there’s any lasting couple, it’s the poet and her favorite goddess. Who does Sappho really love?

“But when she had crossed the stone sill, she sat down by the far wall in the firelight, opposite Odysseus, while he sat by a tall pillar, his eyes on the ground, waiting to see if his wife would speak as she looked at him. She sat there silently for a long time...”

Odysseus und Penelope by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein

Greek philosophy may have idealized Eros, a love based on desire, but Classics professor Margaret Toscano says that the reunion between Odysseus and Penelope at the end of Homer’s Odyssey is more like a miniature romance novel, based on courtship, friendship, and sexual mutuality. Here’s a prose translation of Book XXIII, where they meet again at last. How ancient or modern does their night together seem?

“Neither the herbs of Medea nor the incantations of the Marsi will make love endure. If there were any potency in magic, Medea would have held the son of Æson, Circe would have held Ulysses. Philtres, too, that make the face grow pale, are useless when administered to women. They harm the brain and bring on madness. Away with such criminal devices! If you’d be loved, be worthy to be loved. ”

Ovid’s advice poem Ars Amatoria (The Art of Love) pokes fun at epic poems and philosophy. Here great Caesar’s triumph is a chance to pick up women, and “Know Thyself” means fashion tips (if you’ve got a great tan, show some skin!). Amid the playful amorality, though, there are moments of seriousness. “Love requires art to survive,” he warns women, while chiding male readers “if you want to be loved, be a loveable man.” Rolfe Humphries' 1957 translation brings out the poet’s urbanity, while James Michie’s rhyming version plays up the humor.

To every captive soul and gentle heart

into whose sight this present speech may come,

so that they might write its meaning for me,

greetings, in their lord’s name, who is Love.

Already a third of the hours were almost past

of the time when all the stars were shining,

when Amor suddenly appeared to me

whose memory fills me with terror.

Joyfully Amor seemed to me to hold

my heart in his hand, and held in his arms

my lady wrapped in a cloth sleeping.

Then he woke her, and that burning heart

he fed to her reverently, she fearing,

afterwards he went not to be seen weeping.

-A ciascun´alma presa e gentil core,

Dante's first sonnet in La Vita Nuova

Dante e Beatrice, Salvatore Postiglione

In thirteenth-century Florence, the nine-year-old Dante Alighieri sees Beatrice, also nine, exactly once before Love seizes command of his life. Nine years later, a vision of her in the arms of Love inspires him to write a sonnet—the first in what will be his first great book, La Vita Nuova [The New Life]. But Dante’s love has nothing to do with marriage, intimacy, or tenderness. Would we call it love?

“Passion makes the old medicine new:

Passion lops off the bough of weariness.

Passion is the elixir that renews:

how can there be weariness

when passion is present?

Oh, don’t sigh heavily from fatigue:

seek passion, seek passion, seek passion!”

From the 1990s well into the early 2000s, the bestselling poet in the United States was a 13th century Sufi mystic, Jalaluddin Rumi. Around the world, Rumi’s poems of sacred love have inspired novels, music, and documentary films, as well as spiritual seekers—even as debate swirls about how much of Rumi’s Muslim faith gets lost in the most popular English translations. In 2014, the BBC took note of Rumi’s celebrity status.

In 2012, writing in English, Turkish novelist Elif Shafak wove Rumi’s story of spiritual and poetic awakening into a transformative romance between a middle-aged American housewife and a mysterious foreigner named Aziz Zahara. East meets West, ancient meets modern, and sacred love meets suburban marriage in Forty Rules of Love.

The culture of love in South Asia is ancient, vast, and various, playing out in hundreds of languages, multiple art forms (poetry, song, dance, painting, sculpture, film, and more), and an array of religious traditions. Francine Orsini’s edited collection Love in South Asia: a Cultural History offers a scholarly overview, past and present; if you want to compare loves from East and West, try the award-winning history The Making of Romantic Love, by William Reddy, which compares and contrasts courtly love traditions in Europe, Japan, and eastern India from 900-1200 CE.

The 11th-century Tale of Genji, by Lady Murasaki Shikibu, is sometimes called the world’s first novel, and the pursuits of beauty, poetry, and love—or something like it—are central to the story. Tour the world of the novel in photographs and check out the UNESCO “Heritage Pavilion” for the book, which marks it as a treasure of global culture.

Genji trims young Murasaki's hair while she stands on a go board.

Puritan husbands and wives worried that they would love their spouses more than God—and that God might, in turn, take that human beloved away as punishment. At the Popular Romance Project, Eric Selinger talks about how modern Inspirational romance novels draw on, and turn from, this older tradition of Protestant Christian love.

Nineteenth-century American lovers courted through elaborate rituals of self-criticism, romantic reassurance, and evaluation by family and friends. In Searching the Heart, historian Karen Lystra uses 19th century love letters to trace these patterns, giving an intimate look at love in a restless, transitional time. To read some letters yourself, check out this archive of Civil War love letters at the Missouri Historical Museum.

One of the Missouri History Museum's letter from Captain James Love to his dear Molly

"Death cannot stop true love. All it can do is delay it for a while." - The Princess Bride

When world-renowned Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh talks about “true love,” does he mean the same thing as “true love” in cult movie classic The Princess Bride?

Before you decide, check out the dharma talks here and

The Princess Bride movie site here.

The answers may surprise you!

Love and marriage go together, the song says, like a horse and carriage—but around the world, the two concepts have often been separate, and even at odds. Popular Romance Project advisor Stephanie Coontz explores the vast variety of ideas about what love is and how it relates to marital happiness in the first chapter of Marriage: A History.

British historian Claire Langhammer says that English love went through an “emotional revolution” in the first half of the twentieth century, transforming expectations of marriage and romance and setting the stage for the sexual revolution to follow.

Couples rushed to get married on "love you forever" day (January 4, 2013-- or 13/1/4, which sounds phonetically like "love you forever" in Chinese)

The culture of romantic love in contemporary China is evolving at a dizzying pace. Check out this article, "Chinese Valentine’s Day: A Sign of China’s Rising Love Culture" in Science of Relationships for more information.

Holidays like Valentine’s Day, “I Love You” Day, and “Singles Day” are popular with a young generation, while web-based romance fiction explores ancient and post-modern gender, sexuality, and relationship structures, often through elaborate time-travel plots. Read more here in Jin Feng's paper "Men Conquer the World and Women Save Mankind: Rewriting Patriarchal Traditions through Web-based Matriarchal Romances” in the Journal of Popular Romance Studies.

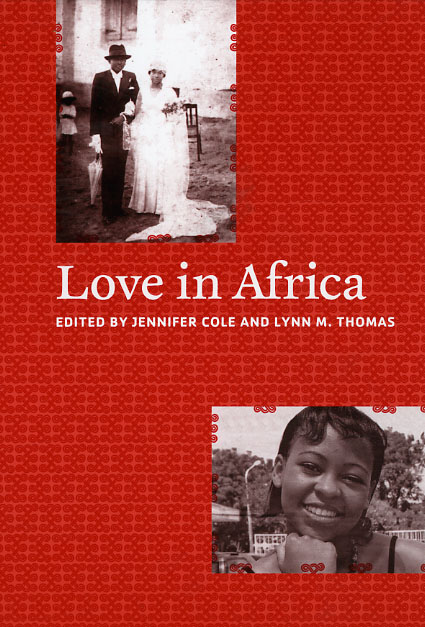

In the introduction to their groundbreaking collection, Love in Africa, Jennifer Cole and Lynn M. Thomas note the curious absence of scholarship outside the continent about the pervasive role of love in African popular culture. From Niger to Zanzibar, the essays in this book explore African-made love media, and also the popularity of Hindi films and Latin American telenovelas with African audiences. Check out the BBC’s article on African romance novels known as “Nollybooks.”

Romance novelist Farida Ado in her home - from Diagram of the Heart by Glenna Gordon

In Diagram of the Heart, photojournalist Glenna Gordon looks at the population of Nigerian women writing “Nollybooks.” These authors often use their novels as a way to comment on the state of Nigerian society, the mores of marriage, and the way that husbands and wives function in Nigeria. Gordon did an interview with the BBC about her time in Nigeria. She includes compelling excerpts from some of the Nollybooks that informed her work.

Husbands and wives didn’t always think that marriage should be “romantic.” Sociologist Eva Illouz explains that advertisers in the 1920s and ‘30s introduced that goal to American consumers, and used coverage of celebrity marriages—especially film stars—to reinforce the ideal.